I have always loved writing letters and cards. If I’m invited to a party, whether that’s a birthday, a goodbye, or another celebration, I feel a little uncomfortably empty-handed if I’ve arrived without a card to give to the host.

During the pandemic, with more time to spend writing (as well as browsing Papier’s overpriced selection of personalised stationery), I got into the habit of writing correspondences to friends for, well, no reason at all really.

I gathered musings on different topics by some of my favourite thinkers and artists, from Mary Oliver on love, to Rainer Maria Rilke on friendship, to James Baldwin on music, and wrote them out by hand to send to friends I thought might appreciate the specific choice of words I’d copied down for them.

It was not a completely selfless act. I found it therapeutic, both selecting the quotes and writing out the letters by hand, running through several 0.38 Muji pens in the process. It helped ground me in the moment and focus on a task at hand when so much else felt out of control. As I type this now, I realise it’s a practice I should get back into—even though my handwriting is notoriously difficult to read.

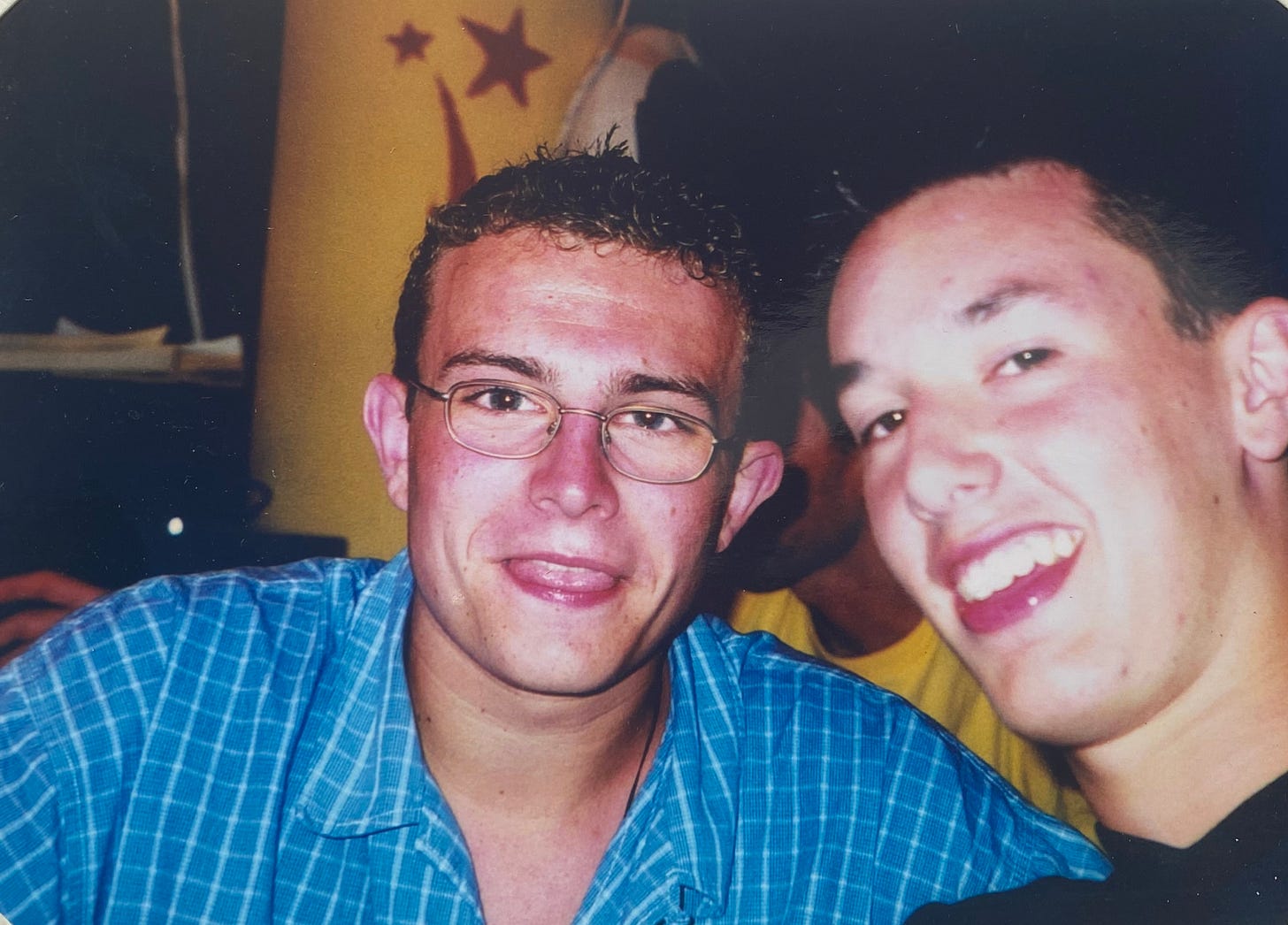

In September 2021, I met up with three of Jonny’s closest friends whom he knew through playing ice hockey. They are three kind, successful and happy men, now in their mid-forties, all with families and children of their own. I know that for my father in particular, it has been too difficult to maintain the relationship he once had with them—not through any fault of theirs, or his. For him, they are living reminders of what could have been, of a life Jonny could have had. I worried that in meeting them now, as an adult rather than a child, I might feel the same way.

And yet, I didn’t. They treated me as an adult, rather than the five year old I had been during the shared trauma they experienced with the loss of their friend. Over Franco Manca pizza and beers on a balmy evening in Covent Garden, I heard through their stories and reminiscence a different side to Jonny; his personality refracted through the prism of their friendship, rather than the familial anecdotes I had grown up hearing.

They told me how he’d excitedly shared his discovery of a “really cool new artist that no one’s heard of yet”, who turned out to be Craig David. They shared their memories of his gentle nature, which almost seems at odds with the aggression and force needed in ice hockey. And we laughed as they looked back on going out to nightclubs and chatting up girls together (something I get the impression he was a little shy at doing).

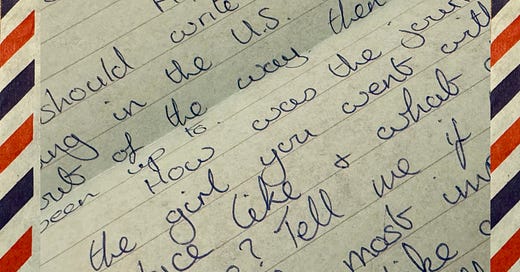

One friend, Josh, gave me a letter that Jonny had written to him during one summer when they were separated—Jonny here at home in London, and Josh away at a summer camp in North Carolina. As Josh placed the letter in my hands, I was overcome with emotions. Here it was, this tangible letter that had been in my brother’s hands, indented with the careful cursive writing that he had spent time compiling.

Even after all these years, Josh kept it perfectly, crisply preserved in an air mail envelope, the kind with the red and blue motif around the border. A postmark from Croydon Post Office marks the date and time it was processed: 1.30pm, 8 September, 1998. Jonny would have been 18 years old.

One of the most painful things about the death of my sibling at the ages we were is the lack of memory I have of him. My inability to figuratively reach into the past and pull out a specific moment in time we spent together has been one of my biggest frustrations with my grief. I have never heard his voice since, or seen a video or moving image of him. Our photographs together are limited. There is no “remember the time when…”—because I simply can’t.

In lieu of this then, the physical objects that Jonny left behind are deeply precious. This relates to our reasons for starting fragments—as I realised that by spending time with his art, I could make sense of how he saw the world.

Yet this letter, written on thin light blue paper in navy biro, was like nothing else I had, another clue as to who he was. And honestly, it’s kind of hilarious.

“First, I will get the questions out of the way,” he opens with, ever courteous, “then tell you what I have been up to.” After a series of questions peppering Josh about life in North Carolina, Jonny ends with the crucial one: “And most importantly of all, what are the girls like out there?”

He continues, sharing updates about hockey, work and college, wishful thinking about holidays, and of course, talking about a girl that he plucked up the courage to ask out on a date. She turned him down, he writes, but he remains resilient: “so now, I’m just going to go out and have a good time.” It’s conversational, chatty, funny—in reading his words and following his pen, crossings out and all, I can hear his 18 year old self speaking the words as he’s writing them down.

Each page is numbered, and the date and our address are at the top of the first—definitely something I would do too. Jonny bids Josh farewell by suggesting they write each other regularly, not just because he wants to hear how America is, but also because “I had to buy a whole packet of air mail envelopes and an air mail writing pad.” Reading this, I notice the top of the paper sheets are slightly jagged from where he’s torn them out of said pad.

As I re-read the letter now, one line stands out to me. Jonny writes about going to a party with friends from college, adding “(See I can still go out, life has not come to a standstill without you.)” Of course, this is a bit of banter between two best friends. But I also think it relates to Jonny’s and my relationship now.

As I’m turning 30 later this year, I’ve been internally tackling the big philosophical questions: Do I need to change my skincare regime? Is that party outfit a bit too much? And to quote Cher, what’s going on with my career? But superseding all of this is the increasing realisation that everything I’ve done, everything I will do, has been for two people, not just for me. That might sound like a lot of pressure. I see it as a gift, a spark, a push to truly live—not slow to a standstill.

Tears falling as Josh gave me this letter, I read part of it aloud. “You sound like him,” one of the friends says. I thank Josh for this gift, a reminder of a time before texting, when reliance on pen and paper prevailed. This letter connects Jonny and I, as does the act of letter writing itself. How sacred it is to be able to hold this fragment, delicate as it is, between my fingertips.

Thank you very much to Josh for sharing this letter with me, and for speaking with me about this newsletter and photographs before its publication.

This is beautiful Suyin x